Almin Zrno: Apologia of Eros

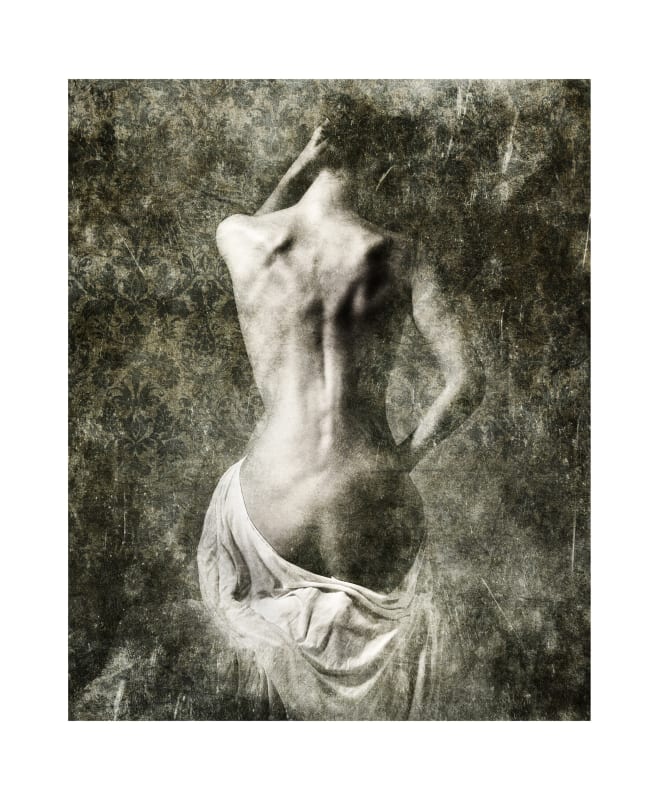

The reception of Almin Zrno’s photographs of nudes from the cycle Frescoes can be read in two keys — as an independent poetics, or as a reflexive poetics juxtaposed to the second cycle of nudes titled Nude. This provides at least a double coded meaning for the photographs. The cycles Nude and Frescoes are in some sense complementary. While the first exposes the body in its physicality, the second cycle brings a transposition of nude photography. Figuratively speaking, while in the first cycle, the female body has a raw and erotic charge making it want to step out of the picture, to touch us, join us, in the second cycle, the body recedes deeper into the picture and exhibits a tendency of disappearance and fragmentation that opens up the question of displacement of aesthetic value. While the first cycle photographs are aesthetically coded, those from the second cycle, while still accentuating the aesthetic, also encroach upon the semantic.

The nude photographs from Frescoes are both formally and semantically geared towards finding a specific link between the figure and the background. Klimt’s Kiss is a model and example from painting of how the two forms blur the boundary to overlap and intertwine in a way that is suggestive of modernist generation of space. In Almin Zrno’s nudes of corporal transposition, the process could better be characterised as postmodern. Here, the body is a figure disappearing, fading into the background, where the solidity of the female body in its erotic tension and beauty is preserved—the body is only at the starting point of a journey towards a specific fragmentation. By merging with the background, the figure seeks to transform itself from its three-dimensional state into a two-dimensional fresco form. The latter also points the way to the dissolution of the image into smaller images, a dispersive and seemingly disorganised composition. Thus, the new “thumbnails” create new nude-accents—-the body is seen from new perspectives. And it is only in this context that the strongest link between these semi-nude draped models in Almin Zrno’s photographs is found, in the guise of ancient spatial and symbolic dimensions. The ambient is one of ancient signification, representations akin to those characteristic of the frescoes found in Ancient Rome, such as the Villa of the Mysteries (Villa dei Misteri in Pompeii). In spite of all their differences, the nudes presented by Zrno are semantically linked to the mysterious female figures of Pompeii. The main semantic thread running between Zrno’s nude transpositions and the female figures from the Villa of the Mysteries is the expression of a secret and its affirmation—maintaining female mystique in its full corporal and erotic, and thus also spiritual, beauty. In a world where every secret is collapsed and lost, where appearances are exposed to their ultimate limits, to the edge of reason, recognising and preserving the inseparable duality of mystery and beauty becomes somewhat of a calling. Besides, mystery is at the heart of examining the meaning of contemporary art, in a space where the transcendental layer of the work of art (Grzegorz Sztabiński) is collapsing and disappearing, the category of mystery is a derivative of the transcendental and possibly its synonym. The situation is similar with the category of beauty, which in contemporary art takes a step back or even completely out of the picture. So the most logical place to preserve mystery is in the beauty of the female form, whose aesthetic dimension, as articulated in the photographs of Almin Zrno, is inextricable from its erotic dimension. Zrno reaffirms classical models and perceptions by also formally linking the category of the beautiful and the erotic with the sacral significance of the female body. Like the depictions of Ancient Greek and Roman goddesses, Zrno’s photographs feature draped semi-nude figures expressive of a gesture. The impression is that Zrno admires the nudes and bows before them.

Zrno’s process for translating the nude from an accentuated aestheticism to the semantic field of the fresco, a mural of ancient signification of the draped nude female body is clearly postmodern. However, “entering the plane of the wall”, transposing the body, its disintegration and dispersion into a two-dimensional format (the wall) is firmly anchored in contemporaneity and its issues. Namely, Zrno withdraws the nude into the background of the image, merging it with the plane of the wall and fashioning it into a fresco-like image. It seems that in contemporary culture and art, the 2D image appears as a specific framework for every visual action, and more importantly, as its very outcome. The psychoanalytic interpretation of contemporary culture could be designated as a desire for the two-dimensional image: “To enter the picture!”, “To become the image!”. This contemporary position (“Be the image!”) is fundamentally different from the aesthetic understanding of the image from the previous epoch in the sense of “Be like the image!”. This facet of contemporary culture (which has still not been assigned the value projection of “good/bad”) is something Zrno affirms with the pointed artificiality of the suggested image, and without concealing it. This becomes quite clear if we juxtapose these nudes, these transpositions of the body and the corporeal, against the previous nudes of exposition (cycle Nude) that use an extreme reification of the female nude to give the sense of coming out of the image, emerging from it into reality itself. In contrast, the photographs of transposed bodies and corporeality (cycle Frescoes) seem to want to reinforce the “aesthetics of disappearance” (Paul Virilio), a vanishing of the material and corporeal world within the space of contemporaneity and its virtualisation.

The aesthetics of disappearance suggest completely different meanings from the ones conveyed by the prominent eros of the female nudes — the distinctive dance of Eros himself. In the shadow of the dancing Eros is the ever-present Thanatos. This insinuation, like a barely noticeable shadow, appears underpinned by the light breath of a fragmented world in the images that disperse the female body and its beauty. Thus, in Almin Zrno’s photographs, the female nude appears—at first glance unexpectedly and contrary to its primary task of a celebration and apologia for the beauty and eroticism of the female body—as a comment and criticism of the contemporary world.

Fehim Hadžimuhamedović