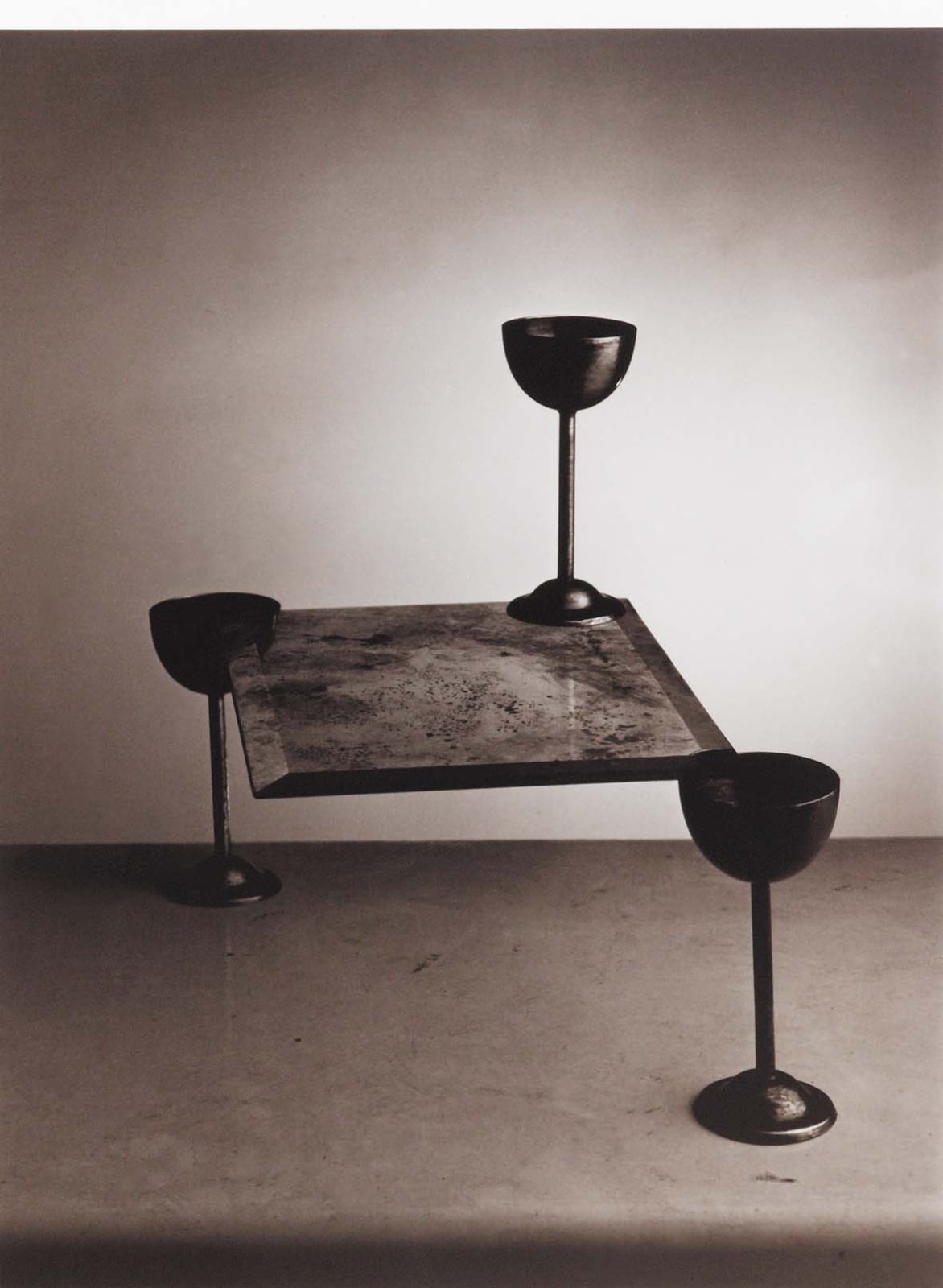

Boris Gaberščik

Svetišče / Sanctuary, 2007

srebroželatinasta fotografija na baritnem papirju, tonirana s selenom / silver gelatine print on baryta paper, selenium toned

19 x 14 cm

edicija 3 + 1 AP / edition of 3 + 1 AP

Series: ORDO AB CHAO

podpisana in datirana / signed and dated

For English version please scroll down. O SERIJI Boris Gaberščik je eden redkih slovenskih umetniških fotografov, ki se posveča fotografiranju tihožitij. Fascinirajo ga učinki, ki jih imajo predmeti drug na...

For English version please scroll down.

O SERIJI

Boris Gaberščik je eden redkih slovenskih umetniških fotografov, ki se posveča fotografiranju tihožitij. Fascinirajo ga učinki, ki jih imajo predmeti drug na drugega, ki izžarevajo mir in tišino, otrplo mirovanje, vpeti ali ujeti v skrivnostno moč oblik. Njegov pristop k mediju je natančen, študiozen in tehnično usmerjen v iskanje najbolj izčiščenih in dovršenih izraznih možnosti. V več kot petindvajsetih letih ustvarjanja je razvil jasen, sistematično izdelan likovni jezik, ki je v naših umetniških krogih nezamenljivo prepoznaven. Gaberščikovo delo izhaja iz čiste oziroma ravne fotografije, ki se je razvila v prvi polovici 20. stoletja v času modernizma (takrat je predstavljala avantgardni pristop) in oblikovala imanentne značilnosti tega vizualnega medija v smislu vsebine, tematike, kompozicije in tehnike. Danes ga označujemo kot tradicionalizem, pri Gaberščiku pa najde izraz v subtilnem poigravanju oziroma oživljanju sveta predmetov v skrbno premišljenih prostorskih razmerjih. Ob prebiranju njegovega fotografskega opusa se spomnimo na dela iz preteklosti, dela uglednih fotografov, kot so Edward Weston, Imogen Cunningham, Walter Petrhans in Josef Sudek, tj. umetnikov, ki so fotografijo povzdignili v enakovreden položaj z drugimi, tradicionalnimi likovnimi umetnostmi in s široko paleto pristopov, posegov (značilnih le za fotografijo) in interpretacij narave, ljudi, predmetov, oblik, prostorov in svetlobe dali vse bolj avtonomnemu mediju nove kompozicijske in pripovedne razsežnosti. Gaberščik se je tem fotografom poklonil tudi z deli z nedvoumnimi naslovi, kot sta Weston’s Kitchen, 2006, in Memory of Josef Sudek, 2005.

Ko iščemo vzporednice z drugimi likovnimi umetnostmi, lahko v Gaberščikovem obravnavanju tematike, oblikovanju vsebin in razporeditvi kompozicij najdemo jasno opredeljena slikarski in kiparski pristop. Dokaz za to so fotografirani predmeti iz njegovega običajnega okolja (nekateri med njimi so stvari iz otroštva), predmeti vsakdanje rabe ali njihovi fragmenti, premišljeno postavljeni in osvetljeni, gledani pod takšnimi koti in v takšnih položajih, da je njihov učinek čim bolj slikovit, plastičen in – kljub črno-beli toniranosti – čim bolj kontrasten in ekspresiven.

Med upodobljenimi predmeti so vijaki, vratne kljuke, deli ključavnic, kosi stekla, skodelice, črepinje, steklenice, pločevinke, svinčniki, jajca, mrtvi insekti (muhe in hrošči), žlice, vilice, sveže ali suho cvetje, deli časopisov, najrazličnejše škatle, fotografski objektivi, ravnila ... Fotograf se jih loteva kot arhitekt, konstruktor oblik, ustvarjalec prostora. Mnogi od teh predmetov so v njegovem življenju igrali pomembno vlogo in hranijo posebne spomine, so skoraj arhetipski in nas vodijo v umetnikov izrazito poetičen in intimen notranji prostor. S premišljeno kompozicijo in osvetlitvijo ti predmeti dobijo dodaten volumen in nekoliko skrivnosten značaj. Združeni so na različnih površinah, ravnih, poševnih ali nagnjenih, v prostorih, ki so večinoma zaprti ali zaprti. Vidni (ali celo grafični) elementi na njihovih površinah so razporejeni v natančno določenih linijah, kar svet fotografije približa svetu slikarstva. O tem je fotograf povedal: »Stare porcelanaste skodelice, zarjaveli kosi železa, posušene rastline in mrtvi insekti, ki sem jih takrat začel načrtno zbirati, so se znašli v moji kleti, na belem polju, prekritem s praskami in udarci. Ko sem te predmete razporedil v točno določena medsebojna razmerja in razdalje ter jih osvetlil z mehko stransko lučjo, sem jasno spoznal ali videl to zvonjenje ... Steklene leče, diagonalno postavljene na osnovno ploščo starega povečevalnika, so postale okna v času in skozi njih sem opazoval, kako se Man Ray in Duchamp ukvarjata z zelo resno partijo šaha.«[1] Slikarski učinki, ki jih imajo takšne fotografije, so kot odsev, ujet med predmeti, razporejenimi v prostoru, in igro svetlobe; to smer nakazujejo tudi nekateri naslovi, npr. Križanje, hommage a Jacopo Tintoretto, 1987, z značilno trikotno kompozicijo Kristusa, ki ga snemajo s križa, skrito v položajih in gubah listov. Podoben učinek imata tudi Grouping for Morandi, 2006, v katerem se predmeti med seboj skrivajo in obrezujejo, in Untitled, 1987, z značilno obliko violine in diagonalno kompozicijo, ki spominja na umetnost Mana Raya. Ta dela (med drugim) poudarjajo, kako premišljeno fotograf oblikuje svoj motivni prostor, pri čemer posveča veliko pozornosti podrobnostim in uporablja (tudi nenavadno) obrezovanje skrbno razporejenih kompozicij z izrazito slikarskim značajem.

Gaberščikove fotografije se navezujejo na zgodbe; so zaokrožene pripovedi, osebni mikrokozmos predmetov z neštetimi podrobnostmi in poudarki, ki so skrbno urejeni. Zgodba sloni na scenografiji predmetov, sestavljenih v instalacije. Ti so med fotografiranjem zapisani na svetlobno občutljiv medij, nato pa jih fotograf takoj razstavi, tako da fotografirani predmeti spet postanejo običajni deli okolja. Ta metoda dela je umetnikova ritualna igra ustvarjanja, premišljeno združevanje različnih predmetov v obrednem plesu za ustvarjanje razpoloženj, ki postanejo pomemben izrazni del njegovih fotografij. Njegova osebna mitologija predmetne resničnosti, njegovo vstajenje sveta mrtvih elementov sta prežeta z njegovo ustvarjalno senco, notranjo močjo predmetov, njihovimi prvobitnimi oblikami, ki jih išče v geometrijskih razmerjih in položajih, nato pa jih uredi v oblike, strukture in končno podobe. Takšne predmetne serije izpostavljajo tudi povezavo med fotografijo in kiparstvom. Poglobljena kontemplacija Gaberščikovih fotografskih tihožitij razkriva njihovo plastičnost in volumen, ki ju ustvarja svetloba; ali kot pravi umetnik: »Strašno sem občutljiv, kar zadeva svetlobo in vse, kar je z njo povezano. Stvari lahko naredim pravilno le v studiu; tam lahko porabim ure, če ne celo dneve, da svetlobo pravilno nastavim in dosežem vsaj del tistega, kar želim v končnem rezultatu. Naravna svetloba mi preprosto ne zadostuje.« [2]

Fotografirani predmeti so v fotografskih tihožitjih videti kot kiparske strukture, npr. v delih Bottle and Black, 1987, M. C. Escher's Space, 2005, Monument (Memorial), 2006, Relic, 2007 ... Masivnost predmetov ustvarja predvsem svetloba, ki običajno pada od strani in poudarja njihov naravni volumen. Uporabljen je en sam vir svetlobe, ki je prilagojen kompoziciji tako, da se ostrina ne zmanjšuje z globino. Prevladuje mehka svetloba, ki poudari ostre obrise in čiste mase predmetov brez močnih senc in kontrastov. Kombinacije predmetov so (le navidezno) preproste, združene v umetnikovi subjektivni vizualni predstavi o predstavljenem. Vendar so položaji praviloma rahlo premaknjeni, odklonjeni ali nagnjeni, dokler se ne zdijo nenavadni, včasih celo kljubujejo gravitaciji. Tu se Gaberščikova tihožitja približajo območju nadrealnega. V kompozicijah se predmeti izogibajo običajnim, pričakovanim ali verjetnim položajem, kar ustvarja podobe vpetega, skrivnostnega vzdušja, kjer se je čas ustavil, kjer so spomini zamrznjeni, predmeti mirujejo, zaznavanje pa se prenaša v polje nadrealističnega intirizma. Svetloba je skrbno nadzorovana, pripuščena v takšnih količinah, da predmeti nimajo odsevov, temveč le postopne tonske prehode. Zaradi tega se zdijo vzvišeni, polni pristne naravne moči, pripadajo svetu oblik, v katerem fotograf vzpostavlja in beleži prefinjen red. V takšnem obvladljivem redu je Boris Gaberščik najbolj doma, saj izdeluje svoj sistem portretov predmetov, potegnjenih v posebno psihološko stanje predmetnosti. To lahko zasledimo v več kot dvesto fotografskih tihožitjih, ki vsa dokazujejo njegov minimalizem pri izbiri motiva in perfekcionizem v odnosu do fotografskega medija.

Gaberščik meni, da je edini način, kako se poglobiti v skrivnosti fotografije, osebna izkušnja, pridobljena v procesu dela. Zato je ustvarjanje zanj dolgotrajen proces priprave, izbire, sestavljanja, razporejanja in združevanja različnih predmetov. Številne fotografije nosijo namenoma indikativne naslove, ki poudarjajo ključni vidik motiva, ideje ali strukture kompozicije. Tako se npr. na fotografiji Orientation of the Tulip, 1987, ohranja negotovo ravnovesje med poševno podlago in cvetom v vazi, ki si z nekakšno notranjo močjo prizadeva za pokončnost. Nekatera dela dajejo poudarek dinamičnemu prepletanju položajev predmetov, nagnjenim kotom, odmikom od realnih (pričakovanih) težnostnih stanj: Miza z igračami, 2005, ima visoko in ozko podporno konstrukcijo, na kateri skodelice navidezno lebdijo v zraku, Magnolija, 2005, pa rahlo (in le navidezno) drsi po nagnjeni površini. Na nekaterih fotografijah so kubični in sferični elementi združeni, sestavljeni in zgrajeni na arhitekturne načine: Na fotografiji Katedrala, 2005, so močni plastični poudarki in dajejo občutek premika težnosti, ki ga ustvarja kontrast svetlobe in teme; na fotografiji Tempelj, 2005, iluzorna podoba preglasi realistične možnosti takšne konstrukcije; na fotografiji Torzo, 2006, pa se zrcali silhueta telesa znotraj konstrukcije iz masivnih elementov.

Tudi bolj angažirane fotografije kažejo na krhkost in minljivost, na primer Država, 1994 in 1999, nestabilna struktura, ki se lahko vsak trenutek zruši, ali Tovarna, 2002, arhitekturna kompozicija kubičnih elementov, ki je izrazito narativna in spominja na preteklost. Veliko fotografij pa je brez naslova; fotograf se je odločil, da gledalcev ne bo usmerjal z naslovom, temveč bo vsakemu omogočil, da si ustvari svojo zgodbo na podlagi osebne izkušnje. In Gaberščikove fotografije vsebujejo številne zgodbe, saj predmeti skrivajo pripovedi o svoji uporabi in »živih« funkcijah v določenem času in prostoru. Predmeti zaživijo z nekakšno notranjo svetlobo, s prirojeno naravno silo, ki jim daje pomen in drug, globok, skorajda metafizičen značaj. To je med drugim mogoče opaziti v objektih Grand Hotel, 1987, Left Flowers, 1987, Pencil for E. A. Poe, 1987, Wassermusik, 1995, Divided View, 1998, Nostalgic Look, 1997, Crushed Snail, 1997, Three Stars, 1995, Contemplation of Form, 2006, Knife on the Water, 2005, in Relic, 2006.

Pri delu v svojem studiu fotograf ustvarja svoj značilno urejen svet predmetov ter ga predstavlja ostro in natančno, z vsemi potrebnimi kontrasti. V primerjavi s takšnimi studijskimi deli so njegove fotografije, posnete na prostem, v naravni svetlobi, veliko manj ostre. Takšne so njegove fotografije v seriji z naslovom Atlantida, Arkadija in Evropa, 2005–2007. Že sami naslovi nakazujejo asociacije na mitološke (mistične) pokrajine, ki izvirajo iz umetnikove domišljije, in realno, otipljivo, določljivo Evropo, v kateri živi in dela. Zunanji svet je zavit v megleno, skrivnostno vzdušje; realne podobe se prebijajo in umikajo, neostre in zamegljene, v kraljestvo fantastike, na cesto (ki prav tako izstopa kot motiv) pravljične igre. Fotograf pravi: »Končal sem s sanjarjenjem o pokrajinah, svetloba mi jih kar naprej jemlje. Izkrivlja jih do neprepoznavnosti; opoldne kot mladenič, poln samega sebe in svoje porajajoče se moči, brezobzirno razdira površine, prežarja lise svetlobe, poglablja sence do diabolične črnine, meša horizont s prvim planom, oddaljuje in spaja stvari, jih splošča in krivi, briše posamezne podrobnosti, zavaja in laže, dokler oči ne zaboli. Instinktivno se umaknem iz fokusa, ublažim hitrost, surovost in neodgovornost ter poiščem sprejemljivejše oblike.« [3]

Narava je polna kontrastov, ki so na prostem veliko močnejši kot v zaprti notranjosti studia. Ko sliko prenesemo na fotografijo, se kontrasti, ki jih je na prostem težje nadzorovati, zmanjšajo. V ateljeju pa je Boris Gaberščik mojster usode predmetov in njihovih kompozicij ter fotografskega dojemanja, povsem ostrega in s premišljenimi svetlobnimi in temnimi učinki. Na tihožitjih ga dodatno obseva notranja svetloba, kot vidimo na fotografiji Dedkova srajca, 2005, kjer je v gubah in kontrastnih gubah tkanine čutiti prisotnost osebe. Srajca je postala metafora za človeka, psihološki portret njenega uporabnika, resničnejši od človeka samega, negiben in živ hkrati.

Boris Gaberščik se je posvetil tudi združevanju fotografij v diptihe in triptihe. Serijo takšnih fotografskih del je poimenoval Dvojina, 2010, Trojina, 2010, in Igra, 2010. S takšnim kompozicijskim postopkom fotograf ustvarja umetniška dela kot nekakšne najdbe, iztrgane iz materialnega sveta, iz sveta, ki ga obdaja in ki zanj pomeni najmočnejšo intuitivno, simbolno, čutno in racionalno povezavo s preteklostjo in sedanjostjo. Ta fotografska dela so stopnjevane ali pomnožene podobe spomina in predstav, s katerimi fotograf razlaga tako svojo likovno poetiko kot svoj najgloblji intimni svet, v katerem se čuti osebno prepoznavnega in ustvarjalnega. Gaberščik je izjemno sistematičen fotograf, njegov opus je obsežen, uravnotežen in zvesto sledi bistveni ideji, ki jo je razvil v številnih fotografskih podobah, namreč da preučuje, odkriva in umešča podobe nekje med svet domišljije in svet resničnosti, nekje med človekom kot subjektom z določenim dojemanjem in svetom določene objektivnosti, ki ga obdaja. Prav ta objektivnost, s katero Gaberščik fotografira, na intenzivno občuten način oživlja polje človekove reprezentacije. Objektivnost, ki je za fotografa tako značilna, je odtis, sled predmeta, dogodka, ki ga je fotograf iztrgal iz določenega življenjskega toka in ga začaral v graduirano podobo.

Fotografirana objektivnost in njene nekoliko drugačne ponovitve ali kombinacije, kot jih predstavljajo ti diptihi in triptihi, se celo približujejo nekemu »krožnemu času magije podob«, v katerem se s fotografskim doživljanjem preteklega časa ohranja ali spodbuja sodobni ali sedanji čas življenja, bivanja nasploh. Fotograf na svoj edinstven način razlaga in si prisvaja svet s podobami predmetnosti, upodobljena predmetnost tako postane spomin, simbolizacija zaznave, v kateri se ustvarjalec počuti močnega, saj vedno znova kodira (zaobjame) izbrano resničnost kot določene koncepte sveta. Tako resničnost kot domišljija, ki skupaj tvorita svobodo ustvarjalne igre, napolnjene s poetiko, značilno za avtorja, in z veliko ustvarjalno močjo, uravnotežita in oživita svet podob, v katerega ali skozi katerega se giblje fotograf.

Prav zaradi te sposobnosti oživljanja predmetnega sveta z zajemanjem najmanjših svetlobnih, tonskih in izraznih stikov med materialnim modelom (predmetom) in končno podobo (fotografijo) je Boris Gaberščik tako edinstven med slovenskimi fotografi. 4 Je umetnik, ki fotografijo obravnava kot medij, ki si zasluži jasen, sistematičen pristop, z velikim občutkom odgovornosti do njenega zgodovinskega razvoja, ki nam daje snov za razmišljanje in užitek v opazovanju.

dr. Sarival Sosič

[1] Boris Gaberščik: Šahovska poteza za M. D. [A chess move for M. D.], Ars vivendi, št. 25, 1995, str. 95–96.

[2] Sašo Scrott: Boris Gaberščik. Fotografija ni le "sklocanje". Intervju. [Photography is more than just snapping away. Interview]. Slovenska panorama, št. 6, 2001, p. 14.

[3] Boris Gaberščik: Uvod. Boris Gaberščik. Ljubljana: Galerija Fotografija, 2005, zloženka.

[4] Boris Gaberščik je v svoji dolgoletni karieri fotografiral veliko število del slovenskih slikarjev in kiparjev. Te fotografije so izšle v monografijah, razstavnih katalogih in drugih umetniških publikacijah.

ABOUT THE SERIES

Boris Gaberščik is one of the few Slovenian art photographers who have dedicated themselves to still lifes. He is fascinated with the effects objects have on one another, emanating peace and quiet, numbly still, engrossed or caught up in the mysterious power of forms. His approach to the medium is precise, studious, and technically oriented at finding the most purified and perfected possibilities of expression. In over twenty-five years of work he has developed a clear, systematically elaborate visual language, unmistakably recognizable in our art circles. Gaberščik’s work derives from the pure, or straight, photography which evolved in the first half of the 20th century in the time of modernism (representing then an avant-garde approach) and formulated this visual medium’s immanent characteristics in terms of content, subject matter, composition, and technique. Today it is referred to as traditionalism, and, in Gaberščik’s case, it finds expression in subtle playing with, or bringing to life, the world of objects in carefully thought-out spatial relations. Looking through his photographic oeuvre we are reminded of works from the past, works of such eminent photographers as Edward Weston, Imogen Cunningham, Walter Petrhans, and Josef Sudek, i.e., the artists who raised photography to a status on a par with the other, traditional visual arts and gave the increasingly autonomous medium new compositional and narrative dimensions with their wide range of approaches to, interventions in (typical only of photography), and interpretations of nature, people, objects, forms, spaces, and light. Gaberščik paid homage to these photographers also with his unambiguously titled works, such as Weston’s Kitchen, 2006, and Memory of Josef Sudek, 2005.

When looking for parallels with other visual arts, we can find a clearly defined painterly and sculptural approach in Gaberščik’s treatment of subject matter, formulation of contents, and arrangement of compositions. Evidence of this are the photographed objects from his ordinary environment (some of them things from his childhood), items of everyday use or their fragments, elaborately positioned and lighted, viewed from such angles and in such positions that the effect they have is as picturesque, plastic, and – despite the black-and-white toning – as contrastivelY,expressive as possible.

Among the portrayed objects there are SCl,”ews, door handles, parts of locks, pieces of glass, of window panes, cups, glass shards, bottles, cans, pencils, eggs, dead insects (flies and bugs), spoons, forks, fresh or dry flowers, sections of newspaper, all manner of boxes, photographic lenses, rulers .:. The photographer addresses them like an architect, a constructor of forms, a creator of space. Many of these objects played an important role in his life and hold special memories, they are almost archetypal, leading us into the artist’s markedly poetic and intimate interior space. With his thoughtful composition and lighting these objects acquire extra volume and a slightly mysterious character. They are brought together on a variety of surfaces, flat, diagonal or tilted, in spaces that are for the most part enclosed or closed. The conspicuous (or even graphic) features on their surfaces are arranged in precisely determined lines, which brings the world of photography close to that of painting. Speaking about this, the photographer has said: “Old china cups, rusty iron pieces, dried plants, and dead insects, which I started to purposefully collect at that time, all ended up in my basement, on a field of white covered with scratches, bumps, and marks. When I arranged these objects in precisely determined relations to, and distances from, one another and lighted them with a soft side light, I clearly realized or saw that ringing … Glass lenses positioned diagonally on the baseboard of an old enlarger became windows in time,• and through them I watched Man Ray and Duchamp going at a very serious game of chess.[1] The painterly effects such photographs have are like reflections caught between objects arranged in space and the play of light, with also some of the titles pointing in that direction, e.g., The Crucifixion, hommage a Jacopo Tintoretto, 1987, with a characteristic triangular composition of Christ being taken down from the Cross hidden in the positions and creases of the leaves. Sharing a similar effect are Grouping for Morandi, 2006, in which the objects hide and crop one another, and Untitled, 1987, with the typical violin. shape and diagonal composition reminiscent of Man Ray’s art. These works (among others) underscore how deliberately the photographer designs his motif space, giving a great deal of attention to details and using an (also unusual) cropping of carefully arranged compositions with an emphatically painterly character.

Gaberščik’s photographs relate to stories; they are well-rounded narratives, a personal microcosm of objects with myriad details and emphases, carefully organized. The story rests on a set design of objects composed in what are virtually installations. These are recorded on a lightsensitive medium in the act of photographing and then immediately taken apart by the photographer so that the photographed objects again become ordinary parts of the environment. This work method is the artist’s ritual game of creation, a thoughtful coupling of various objects in a ritual dance to produce moods that become an important expressive part of his photographs. His personal mythology of object reality, his resurrection of the world of dead elements are suffused with his creative shadow, the inner power of objects, their primordial forms sought out in geometric relations and positions, and then arranged into shapes, structures, and finally, images. Such subject matter series also bring out the link between photography and sculpture. A profound contemplation of Gaberščik’s photographic still lifes reveals their plasticity and volume, which are created by light; or as the artists says: “I’m terribly sensitive as regards light and everything related to it. I can only do things right in the studio; there I can spend hours, if not days, getting the light right to achieve at least part of what I want in the end result. For me, natural light is simply insufficient.” [2]

The photographed objects appear like sculptural structures in the photographic stilllifes, e.g., in the works Bottle and Black, 1987, M. C. Escher’s Space, 2005, Monument (Memorial), 2006, Relic, 2007 … The massiveness of the objects is produced principally by light, usually falling from the side and emphasizing their natural volume. A single light source is used, adjusted to the composition in such a way that the sharpness does not decrease with depth. Soft light predominates, bringing out sharp contours and pure masses of objects, without strong shadows and contrasts. The combinations of objects are (only apparently) simple, brought together in the artist’s subjective visual idea of the represented. However, as a rule, the positions are slightly shifted, deviated, slanted, or tilted, until they seem unusual, sometimes even defying gravity. This is where Gaberščik’s stilllifes come close to the realm of the surreal. In the compositions, the objects eschew ordinary, expected, or probable positions, producing images of an absorbed, mysterious atmosphere, where time has stopped, where memories are frozen, the objects stock still, and perception is transferred to the field of surrealist intirnism. Light is carefully controlled, admitted in such amounts that the objects do not have reflections, only gradual tonal transitions. This makes them appear elevated, full of a genuine natural power, belonging to a world of forms in which the photographer establishes and records a refined order. Such a controllable order is where Boris Gaberščik is most at home, working out his own system of portraits of objects drawn into a special psychological state of objecthood. This can be traced in over two hundred photographic still lifes, all evidencing his minimalism in the choice of motif and his perfectionism in relation to the medium of photography.

For Gaberščik, the only way to fathom the mysteries of photography is by personal experience gained in the process of work. That is why for him creating is a drawn-out process of preparing, choosing, composing, arranging, and uniting different objects. Many photographs bear deliberately indicative titles, emphasizing a crucial aspect of the motif, or the idea, or the structure of the composition. Thus, e.g., in the Orientation of the Tulip, 1987, a precarious balance is maintained between the slanting base and the flower in a vase which strives toward uprightness with some kind of inner strength. Some works give emphasis to the dynamic interplay of the objects’ positions, tilted angles, departures from real (expected) states of gravity: Arrangement for Irwin Penn, 1992, consists of a mass of elements that appear to have loosened up; Table with Toys, 2005, has a tall and narrow supporting structure on which cups seemingly hover in the air; and Magnolia, 2005, slightly (and only apparently) slides down an inclined surface. In some photographs, cubic and spherical elements are brought together, assembled and constructed in architectural ways: Cathedral, 2005, has strong plastic emphases and gives a sense of gravity shift produced by the contrasting of light and dark; in Temple, 2005, the illusory image overrides the realistic possibilities of such a construction; and Torso, 2006, reflects the silhouette of . a body inside a construction of massive elements. Also the more engaged photographs indicate fragility and transience, e.g., the State, 1994 and 1999, an unstable structure that could topple at any moment, or the Factory, 2002, an architectural composition of cubic elements, markedly narrative and reminiscent of the past. A great number of photographs, however, are Untitled; the photographer chose not to direct viewers with a title, allowing instead everyone to create their own story based on their personal experience. And Gaberščik’s photographs contain many stories, with the objects concealing the narratives of their use and “lived” functions in a certain time and place. The objects are brought to life with a certain kind of inner light, an inherent natural force that gives them meaning and another, profound, almost metaphysical character. This is observable in Grand Hotel, 1987, Left Flowers, 1987, Pencil for E. A. Poe, 1987, Wassermusik, 1995, Divided View, 1998, Nostalgic Look, 1997, Crushed Snail, 1997, Three Stars, 1995, Contemplation of Form, 2006, Knife on the Water, 2005, and Relic, 2006, among others.

Working in his studio, the photographer creates his characteristically ordered world of objects and presents it sharply and precisely, with all the necessary contrasts. Compared to such studio works, his photographs taken outdoors, in natural light, are far less sharp. Such are his photographs in the series entitled Atlantis, Arcadia, and Europe, 2005-2007. The titles themselves indicate associations with mythological (mystical) landscapes originating in the artist’s imagination and the real, tangible, definable Europe, in which he lives and works. The exterior world is enveloped in a hazy, mysterious atmosphere; real images push through and retreat, unfocused and blurry, into the realm of the fantastic, onto the road (which also stands out as a motif) of fairy tale play. The photographer says: “I’m through with dreaming of landscapes, the light keeps taking them away from me. It distorts them to a point beyond recognizability; noontime, like a youth full of himself and his budding power, heedlessly tears up surfaces, burns through patches of light, deepens the shadows to diabolic blackness, blends the horizon with the foreground, distances and fuses things, flattens and curves them, erases individual details, deceives and lies until the eyes are in pain. Instinctively I retreat out of focus, easing the speed, the harshness, and the irresponsibility, and look for more tolerable forms.” [3]

Nature is full of contrasts, which are much stronger outdoors than in the closed studio interior. When an image is transferred to a photograph, the contrasts, more difficult to control outdoors, diminish. But in his studio, Boris Gaberščik is the master of the fate of objects and their compositions, and of his photographic perception, totally sharp and with elaborate light and dark effects. The stilllifes are additionally irradiated by an inner light, as we can see in the photograph Grandfather’s Shirt, 2005, where the presence of the person can be felt in the folds and contrast creases of the fabric. The shirt has become a metaphor for the man, a psychological portrait of its wearer, more real than the man himself, motionless and alive at the same time.

Boris Gaberščik has been in the recent years combining photographs into diptychs and triptychs. He calls the series of such photographic works Dvojina (Dual), 2010, Trojina (Trinity), 2010, and Igra (Play), 2010. By such compositional procedure the photographer creates works of art as some kinds of finds, torn from the material world, from the world which surrounds him, and which for him signifies the strongest intuitive, symbolic, sensual and rational link with the past and the present. These photographic works are gradated or multiplied images of memory and representations with which the photographer explains both his fine art poetics and his innermost intimate world, in which he feels he is personally recognisable and creative. Gaberščik is exceptionally systematic photographer, his opus is extensive, balanced and faithfully follows the essential idea he has developed in numerous photographic images, namely that he studies, discovers and places images somewhere between the world of imagination and the world of reality, somewhere between the man as a subject with defined perception and the world of certain objectivity that surrounds him. It is this objectivity, with which Gaberščik photographs, that animates in an intensely felt way the man’s field of representation. The objectivity so characteristic for the photographer is a print, a trace of an object, an event which the photographer has torn from the particular flow of life, spellbound it into a graduated image. The photographed objectivity and its slightly different repetitions or combinations, as presented by these diptychs and triptychs, even approaches some »circular time of the magic of images«, in which – through photographic experiencing of the past time – the modern or present time of life, existence in general, is preserved or encouraged. The photographer explains and appropriates in his unique way the world with the images of objectivity, the depicted objectivity thus becomes a memory, symbolization of perception, in which the creator feels strong, as he ever anew encodes (embraces) the selected reality as certain concepts of the world. Both reality and imagination, which together form the freedom of a creative game filled with poetics characteristic for the author and with great creative force, balance and animate the world of images into which or through which moves the photographer.

It is this ability to bring the object world alive by capturing the minutest light, tonal, and expressive contacts between the material model (the subject) and the final image (the photograph) that makes Boris Gaberščik[4]so unique among Slovenian photographers. He is an artist who treats photography as a medium deserving a clear, systematic approach, with a great sense of responsibility toward its historical development, giving us food for thought and pleasure in observation.

Sarival Sosič, PhD

[1] Boris Gaberščik: Šahovska poteza za M. D. [A chess move for M. D.] Ars vivendi, St. 25, 1995, pp 95-96

[2] Sašo Scrott: Boris Gaberščik. Fotografija ni le “sklocanje”. Intervju. [Photography is more than just snapping away. Interview]. Slovenksa panorama, št. 6,2001, p.14

[3] Boris Gaberščik: Introduction. Boris Gaberščik. Ljubljana: Galerija Fotografija, 2005, leaflet [4] In his long career Boris Gaberščik has photographed a great number of works by Slovenian painters and sculptors. These photographs have appeared in monographs, exhibition catalogues, and other art publications.

O SERIJI

Boris Gaberščik je eden redkih slovenskih umetniških fotografov, ki se posveča fotografiranju tihožitij. Fascinirajo ga učinki, ki jih imajo predmeti drug na drugega, ki izžarevajo mir in tišino, otrplo mirovanje, vpeti ali ujeti v skrivnostno moč oblik. Njegov pristop k mediju je natančen, študiozen in tehnično usmerjen v iskanje najbolj izčiščenih in dovršenih izraznih možnosti. V več kot petindvajsetih letih ustvarjanja je razvil jasen, sistematično izdelan likovni jezik, ki je v naših umetniških krogih nezamenljivo prepoznaven. Gaberščikovo delo izhaja iz čiste oziroma ravne fotografije, ki se je razvila v prvi polovici 20. stoletja v času modernizma (takrat je predstavljala avantgardni pristop) in oblikovala imanentne značilnosti tega vizualnega medija v smislu vsebine, tematike, kompozicije in tehnike. Danes ga označujemo kot tradicionalizem, pri Gaberščiku pa najde izraz v subtilnem poigravanju oziroma oživljanju sveta predmetov v skrbno premišljenih prostorskih razmerjih. Ob prebiranju njegovega fotografskega opusa se spomnimo na dela iz preteklosti, dela uglednih fotografov, kot so Edward Weston, Imogen Cunningham, Walter Petrhans in Josef Sudek, tj. umetnikov, ki so fotografijo povzdignili v enakovreden položaj z drugimi, tradicionalnimi likovnimi umetnostmi in s široko paleto pristopov, posegov (značilnih le za fotografijo) in interpretacij narave, ljudi, predmetov, oblik, prostorov in svetlobe dali vse bolj avtonomnemu mediju nove kompozicijske in pripovedne razsežnosti. Gaberščik se je tem fotografom poklonil tudi z deli z nedvoumnimi naslovi, kot sta Weston’s Kitchen, 2006, in Memory of Josef Sudek, 2005.

Ko iščemo vzporednice z drugimi likovnimi umetnostmi, lahko v Gaberščikovem obravnavanju tematike, oblikovanju vsebin in razporeditvi kompozicij najdemo jasno opredeljena slikarski in kiparski pristop. Dokaz za to so fotografirani predmeti iz njegovega običajnega okolja (nekateri med njimi so stvari iz otroštva), predmeti vsakdanje rabe ali njihovi fragmenti, premišljeno postavljeni in osvetljeni, gledani pod takšnimi koti in v takšnih položajih, da je njihov učinek čim bolj slikovit, plastičen in – kljub črno-beli toniranosti – čim bolj kontrasten in ekspresiven.

Med upodobljenimi predmeti so vijaki, vratne kljuke, deli ključavnic, kosi stekla, skodelice, črepinje, steklenice, pločevinke, svinčniki, jajca, mrtvi insekti (muhe in hrošči), žlice, vilice, sveže ali suho cvetje, deli časopisov, najrazličnejše škatle, fotografski objektivi, ravnila ... Fotograf se jih loteva kot arhitekt, konstruktor oblik, ustvarjalec prostora. Mnogi od teh predmetov so v njegovem življenju igrali pomembno vlogo in hranijo posebne spomine, so skoraj arhetipski in nas vodijo v umetnikov izrazito poetičen in intimen notranji prostor. S premišljeno kompozicijo in osvetlitvijo ti predmeti dobijo dodaten volumen in nekoliko skrivnosten značaj. Združeni so na različnih površinah, ravnih, poševnih ali nagnjenih, v prostorih, ki so večinoma zaprti ali zaprti. Vidni (ali celo grafični) elementi na njihovih površinah so razporejeni v natančno določenih linijah, kar svet fotografije približa svetu slikarstva. O tem je fotograf povedal: »Stare porcelanaste skodelice, zarjaveli kosi železa, posušene rastline in mrtvi insekti, ki sem jih takrat začel načrtno zbirati, so se znašli v moji kleti, na belem polju, prekritem s praskami in udarci. Ko sem te predmete razporedil v točno določena medsebojna razmerja in razdalje ter jih osvetlil z mehko stransko lučjo, sem jasno spoznal ali videl to zvonjenje ... Steklene leče, diagonalno postavljene na osnovno ploščo starega povečevalnika, so postale okna v času in skozi njih sem opazoval, kako se Man Ray in Duchamp ukvarjata z zelo resno partijo šaha.«[1] Slikarski učinki, ki jih imajo takšne fotografije, so kot odsev, ujet med predmeti, razporejenimi v prostoru, in igro svetlobe; to smer nakazujejo tudi nekateri naslovi, npr. Križanje, hommage a Jacopo Tintoretto, 1987, z značilno trikotno kompozicijo Kristusa, ki ga snemajo s križa, skrito v položajih in gubah listov. Podoben učinek imata tudi Grouping for Morandi, 2006, v katerem se predmeti med seboj skrivajo in obrezujejo, in Untitled, 1987, z značilno obliko violine in diagonalno kompozicijo, ki spominja na umetnost Mana Raya. Ta dela (med drugim) poudarjajo, kako premišljeno fotograf oblikuje svoj motivni prostor, pri čemer posveča veliko pozornosti podrobnostim in uporablja (tudi nenavadno) obrezovanje skrbno razporejenih kompozicij z izrazito slikarskim značajem.

Gaberščikove fotografije se navezujejo na zgodbe; so zaokrožene pripovedi, osebni mikrokozmos predmetov z neštetimi podrobnostmi in poudarki, ki so skrbno urejeni. Zgodba sloni na scenografiji predmetov, sestavljenih v instalacije. Ti so med fotografiranjem zapisani na svetlobno občutljiv medij, nato pa jih fotograf takoj razstavi, tako da fotografirani predmeti spet postanejo običajni deli okolja. Ta metoda dela je umetnikova ritualna igra ustvarjanja, premišljeno združevanje različnih predmetov v obrednem plesu za ustvarjanje razpoloženj, ki postanejo pomemben izrazni del njegovih fotografij. Njegova osebna mitologija predmetne resničnosti, njegovo vstajenje sveta mrtvih elementov sta prežeta z njegovo ustvarjalno senco, notranjo močjo predmetov, njihovimi prvobitnimi oblikami, ki jih išče v geometrijskih razmerjih in položajih, nato pa jih uredi v oblike, strukture in končno podobe. Takšne predmetne serije izpostavljajo tudi povezavo med fotografijo in kiparstvom. Poglobljena kontemplacija Gaberščikovih fotografskih tihožitij razkriva njihovo plastičnost in volumen, ki ju ustvarja svetloba; ali kot pravi umetnik: »Strašno sem občutljiv, kar zadeva svetlobo in vse, kar je z njo povezano. Stvari lahko naredim pravilno le v studiu; tam lahko porabim ure, če ne celo dneve, da svetlobo pravilno nastavim in dosežem vsaj del tistega, kar želim v končnem rezultatu. Naravna svetloba mi preprosto ne zadostuje.« [2]

Fotografirani predmeti so v fotografskih tihožitjih videti kot kiparske strukture, npr. v delih Bottle and Black, 1987, M. C. Escher's Space, 2005, Monument (Memorial), 2006, Relic, 2007 ... Masivnost predmetov ustvarja predvsem svetloba, ki običajno pada od strani in poudarja njihov naravni volumen. Uporabljen je en sam vir svetlobe, ki je prilagojen kompoziciji tako, da se ostrina ne zmanjšuje z globino. Prevladuje mehka svetloba, ki poudari ostre obrise in čiste mase predmetov brez močnih senc in kontrastov. Kombinacije predmetov so (le navidezno) preproste, združene v umetnikovi subjektivni vizualni predstavi o predstavljenem. Vendar so položaji praviloma rahlo premaknjeni, odklonjeni ali nagnjeni, dokler se ne zdijo nenavadni, včasih celo kljubujejo gravitaciji. Tu se Gaberščikova tihožitja približajo območju nadrealnega. V kompozicijah se predmeti izogibajo običajnim, pričakovanim ali verjetnim položajem, kar ustvarja podobe vpetega, skrivnostnega vzdušja, kjer se je čas ustavil, kjer so spomini zamrznjeni, predmeti mirujejo, zaznavanje pa se prenaša v polje nadrealističnega intirizma. Svetloba je skrbno nadzorovana, pripuščena v takšnih količinah, da predmeti nimajo odsevov, temveč le postopne tonske prehode. Zaradi tega se zdijo vzvišeni, polni pristne naravne moči, pripadajo svetu oblik, v katerem fotograf vzpostavlja in beleži prefinjen red. V takšnem obvladljivem redu je Boris Gaberščik najbolj doma, saj izdeluje svoj sistem portretov predmetov, potegnjenih v posebno psihološko stanje predmetnosti. To lahko zasledimo v več kot dvesto fotografskih tihožitjih, ki vsa dokazujejo njegov minimalizem pri izbiri motiva in perfekcionizem v odnosu do fotografskega medija.

Gaberščik meni, da je edini način, kako se poglobiti v skrivnosti fotografije, osebna izkušnja, pridobljena v procesu dela. Zato je ustvarjanje zanj dolgotrajen proces priprave, izbire, sestavljanja, razporejanja in združevanja različnih predmetov. Številne fotografije nosijo namenoma indikativne naslove, ki poudarjajo ključni vidik motiva, ideje ali strukture kompozicije. Tako se npr. na fotografiji Orientation of the Tulip, 1987, ohranja negotovo ravnovesje med poševno podlago in cvetom v vazi, ki si z nekakšno notranjo močjo prizadeva za pokončnost. Nekatera dela dajejo poudarek dinamičnemu prepletanju položajev predmetov, nagnjenim kotom, odmikom od realnih (pričakovanih) težnostnih stanj: Miza z igračami, 2005, ima visoko in ozko podporno konstrukcijo, na kateri skodelice navidezno lebdijo v zraku, Magnolija, 2005, pa rahlo (in le navidezno) drsi po nagnjeni površini. Na nekaterih fotografijah so kubični in sferični elementi združeni, sestavljeni in zgrajeni na arhitekturne načine: Na fotografiji Katedrala, 2005, so močni plastični poudarki in dajejo občutek premika težnosti, ki ga ustvarja kontrast svetlobe in teme; na fotografiji Tempelj, 2005, iluzorna podoba preglasi realistične možnosti takšne konstrukcije; na fotografiji Torzo, 2006, pa se zrcali silhueta telesa znotraj konstrukcije iz masivnih elementov.

Tudi bolj angažirane fotografije kažejo na krhkost in minljivost, na primer Država, 1994 in 1999, nestabilna struktura, ki se lahko vsak trenutek zruši, ali Tovarna, 2002, arhitekturna kompozicija kubičnih elementov, ki je izrazito narativna in spominja na preteklost. Veliko fotografij pa je brez naslova; fotograf se je odločil, da gledalcev ne bo usmerjal z naslovom, temveč bo vsakemu omogočil, da si ustvari svojo zgodbo na podlagi osebne izkušnje. In Gaberščikove fotografije vsebujejo številne zgodbe, saj predmeti skrivajo pripovedi o svoji uporabi in »živih« funkcijah v določenem času in prostoru. Predmeti zaživijo z nekakšno notranjo svetlobo, s prirojeno naravno silo, ki jim daje pomen in drug, globok, skorajda metafizičen značaj. To je med drugim mogoče opaziti v objektih Grand Hotel, 1987, Left Flowers, 1987, Pencil for E. A. Poe, 1987, Wassermusik, 1995, Divided View, 1998, Nostalgic Look, 1997, Crushed Snail, 1997, Three Stars, 1995, Contemplation of Form, 2006, Knife on the Water, 2005, in Relic, 2006.

Pri delu v svojem studiu fotograf ustvarja svoj značilno urejen svet predmetov ter ga predstavlja ostro in natančno, z vsemi potrebnimi kontrasti. V primerjavi s takšnimi studijskimi deli so njegove fotografije, posnete na prostem, v naravni svetlobi, veliko manj ostre. Takšne so njegove fotografije v seriji z naslovom Atlantida, Arkadija in Evropa, 2005–2007. Že sami naslovi nakazujejo asociacije na mitološke (mistične) pokrajine, ki izvirajo iz umetnikove domišljije, in realno, otipljivo, določljivo Evropo, v kateri živi in dela. Zunanji svet je zavit v megleno, skrivnostno vzdušje; realne podobe se prebijajo in umikajo, neostre in zamegljene, v kraljestvo fantastike, na cesto (ki prav tako izstopa kot motiv) pravljične igre. Fotograf pravi: »Končal sem s sanjarjenjem o pokrajinah, svetloba mi jih kar naprej jemlje. Izkrivlja jih do neprepoznavnosti; opoldne kot mladenič, poln samega sebe in svoje porajajoče se moči, brezobzirno razdira površine, prežarja lise svetlobe, poglablja sence do diabolične črnine, meša horizont s prvim planom, oddaljuje in spaja stvari, jih splošča in krivi, briše posamezne podrobnosti, zavaja in laže, dokler oči ne zaboli. Instinktivno se umaknem iz fokusa, ublažim hitrost, surovost in neodgovornost ter poiščem sprejemljivejše oblike.« [3]

Narava je polna kontrastov, ki so na prostem veliko močnejši kot v zaprti notranjosti studia. Ko sliko prenesemo na fotografijo, se kontrasti, ki jih je na prostem težje nadzorovati, zmanjšajo. V ateljeju pa je Boris Gaberščik mojster usode predmetov in njihovih kompozicij ter fotografskega dojemanja, povsem ostrega in s premišljenimi svetlobnimi in temnimi učinki. Na tihožitjih ga dodatno obseva notranja svetloba, kot vidimo na fotografiji Dedkova srajca, 2005, kjer je v gubah in kontrastnih gubah tkanine čutiti prisotnost osebe. Srajca je postala metafora za človeka, psihološki portret njenega uporabnika, resničnejši od človeka samega, negiben in živ hkrati.

Boris Gaberščik se je posvetil tudi združevanju fotografij v diptihe in triptihe. Serijo takšnih fotografskih del je poimenoval Dvojina, 2010, Trojina, 2010, in Igra, 2010. S takšnim kompozicijskim postopkom fotograf ustvarja umetniška dela kot nekakšne najdbe, iztrgane iz materialnega sveta, iz sveta, ki ga obdaja in ki zanj pomeni najmočnejšo intuitivno, simbolno, čutno in racionalno povezavo s preteklostjo in sedanjostjo. Ta fotografska dela so stopnjevane ali pomnožene podobe spomina in predstav, s katerimi fotograf razlaga tako svojo likovno poetiko kot svoj najgloblji intimni svet, v katerem se čuti osebno prepoznavnega in ustvarjalnega. Gaberščik je izjemno sistematičen fotograf, njegov opus je obsežen, uravnotežen in zvesto sledi bistveni ideji, ki jo je razvil v številnih fotografskih podobah, namreč da preučuje, odkriva in umešča podobe nekje med svet domišljije in svet resničnosti, nekje med človekom kot subjektom z določenim dojemanjem in svetom določene objektivnosti, ki ga obdaja. Prav ta objektivnost, s katero Gaberščik fotografira, na intenzivno občuten način oživlja polje človekove reprezentacije. Objektivnost, ki je za fotografa tako značilna, je odtis, sled predmeta, dogodka, ki ga je fotograf iztrgal iz določenega življenjskega toka in ga začaral v graduirano podobo.

Fotografirana objektivnost in njene nekoliko drugačne ponovitve ali kombinacije, kot jih predstavljajo ti diptihi in triptihi, se celo približujejo nekemu »krožnemu času magije podob«, v katerem se s fotografskim doživljanjem preteklega časa ohranja ali spodbuja sodobni ali sedanji čas življenja, bivanja nasploh. Fotograf na svoj edinstven način razlaga in si prisvaja svet s podobami predmetnosti, upodobljena predmetnost tako postane spomin, simbolizacija zaznave, v kateri se ustvarjalec počuti močnega, saj vedno znova kodira (zaobjame) izbrano resničnost kot določene koncepte sveta. Tako resničnost kot domišljija, ki skupaj tvorita svobodo ustvarjalne igre, napolnjene s poetiko, značilno za avtorja, in z veliko ustvarjalno močjo, uravnotežita in oživita svet podob, v katerega ali skozi katerega se giblje fotograf.

Prav zaradi te sposobnosti oživljanja predmetnega sveta z zajemanjem najmanjših svetlobnih, tonskih in izraznih stikov med materialnim modelom (predmetom) in končno podobo (fotografijo) je Boris Gaberščik tako edinstven med slovenskimi fotografi. 4 Je umetnik, ki fotografijo obravnava kot medij, ki si zasluži jasen, sistematičen pristop, z velikim občutkom odgovornosti do njenega zgodovinskega razvoja, ki nam daje snov za razmišljanje in užitek v opazovanju.

dr. Sarival Sosič

[1] Boris Gaberščik: Šahovska poteza za M. D. [A chess move for M. D.], Ars vivendi, št. 25, 1995, str. 95–96.

[2] Sašo Scrott: Boris Gaberščik. Fotografija ni le "sklocanje". Intervju. [Photography is more than just snapping away. Interview]. Slovenska panorama, št. 6, 2001, p. 14.

[3] Boris Gaberščik: Uvod. Boris Gaberščik. Ljubljana: Galerija Fotografija, 2005, zloženka.

[4] Boris Gaberščik je v svoji dolgoletni karieri fotografiral veliko število del slovenskih slikarjev in kiparjev. Te fotografije so izšle v monografijah, razstavnih katalogih in drugih umetniških publikacijah.

ABOUT THE SERIES

Boris Gaberščik is one of the few Slovenian art photographers who have dedicated themselves to still lifes. He is fascinated with the effects objects have on one another, emanating peace and quiet, numbly still, engrossed or caught up in the mysterious power of forms. His approach to the medium is precise, studious, and technically oriented at finding the most purified and perfected possibilities of expression. In over twenty-five years of work he has developed a clear, systematically elaborate visual language, unmistakably recognizable in our art circles. Gaberščik’s work derives from the pure, or straight, photography which evolved in the first half of the 20th century in the time of modernism (representing then an avant-garde approach) and formulated this visual medium’s immanent characteristics in terms of content, subject matter, composition, and technique. Today it is referred to as traditionalism, and, in Gaberščik’s case, it finds expression in subtle playing with, or bringing to life, the world of objects in carefully thought-out spatial relations. Looking through his photographic oeuvre we are reminded of works from the past, works of such eminent photographers as Edward Weston, Imogen Cunningham, Walter Petrhans, and Josef Sudek, i.e., the artists who raised photography to a status on a par with the other, traditional visual arts and gave the increasingly autonomous medium new compositional and narrative dimensions with their wide range of approaches to, interventions in (typical only of photography), and interpretations of nature, people, objects, forms, spaces, and light. Gaberščik paid homage to these photographers also with his unambiguously titled works, such as Weston’s Kitchen, 2006, and Memory of Josef Sudek, 2005.

When looking for parallels with other visual arts, we can find a clearly defined painterly and sculptural approach in Gaberščik’s treatment of subject matter, formulation of contents, and arrangement of compositions. Evidence of this are the photographed objects from his ordinary environment (some of them things from his childhood), items of everyday use or their fragments, elaborately positioned and lighted, viewed from such angles and in such positions that the effect they have is as picturesque, plastic, and – despite the black-and-white toning – as contrastivelY,expressive as possible.

Among the portrayed objects there are SCl,”ews, door handles, parts of locks, pieces of glass, of window panes, cups, glass shards, bottles, cans, pencils, eggs, dead insects (flies and bugs), spoons, forks, fresh or dry flowers, sections of newspaper, all manner of boxes, photographic lenses, rulers .:. The photographer addresses them like an architect, a constructor of forms, a creator of space. Many of these objects played an important role in his life and hold special memories, they are almost archetypal, leading us into the artist’s markedly poetic and intimate interior space. With his thoughtful composition and lighting these objects acquire extra volume and a slightly mysterious character. They are brought together on a variety of surfaces, flat, diagonal or tilted, in spaces that are for the most part enclosed or closed. The conspicuous (or even graphic) features on their surfaces are arranged in precisely determined lines, which brings the world of photography close to that of painting. Speaking about this, the photographer has said: “Old china cups, rusty iron pieces, dried plants, and dead insects, which I started to purposefully collect at that time, all ended up in my basement, on a field of white covered with scratches, bumps, and marks. When I arranged these objects in precisely determined relations to, and distances from, one another and lighted them with a soft side light, I clearly realized or saw that ringing … Glass lenses positioned diagonally on the baseboard of an old enlarger became windows in time,• and through them I watched Man Ray and Duchamp going at a very serious game of chess.[1] The painterly effects such photographs have are like reflections caught between objects arranged in space and the play of light, with also some of the titles pointing in that direction, e.g., The Crucifixion, hommage a Jacopo Tintoretto, 1987, with a characteristic triangular composition of Christ being taken down from the Cross hidden in the positions and creases of the leaves. Sharing a similar effect are Grouping for Morandi, 2006, in which the objects hide and crop one another, and Untitled, 1987, with the typical violin. shape and diagonal composition reminiscent of Man Ray’s art. These works (among others) underscore how deliberately the photographer designs his motif space, giving a great deal of attention to details and using an (also unusual) cropping of carefully arranged compositions with an emphatically painterly character.

Gaberščik’s photographs relate to stories; they are well-rounded narratives, a personal microcosm of objects with myriad details and emphases, carefully organized. The story rests on a set design of objects composed in what are virtually installations. These are recorded on a lightsensitive medium in the act of photographing and then immediately taken apart by the photographer so that the photographed objects again become ordinary parts of the environment. This work method is the artist’s ritual game of creation, a thoughtful coupling of various objects in a ritual dance to produce moods that become an important expressive part of his photographs. His personal mythology of object reality, his resurrection of the world of dead elements are suffused with his creative shadow, the inner power of objects, their primordial forms sought out in geometric relations and positions, and then arranged into shapes, structures, and finally, images. Such subject matter series also bring out the link between photography and sculpture. A profound contemplation of Gaberščik’s photographic still lifes reveals their plasticity and volume, which are created by light; or as the artists says: “I’m terribly sensitive as regards light and everything related to it. I can only do things right in the studio; there I can spend hours, if not days, getting the light right to achieve at least part of what I want in the end result. For me, natural light is simply insufficient.” [2]

The photographed objects appear like sculptural structures in the photographic stilllifes, e.g., in the works Bottle and Black, 1987, M. C. Escher’s Space, 2005, Monument (Memorial), 2006, Relic, 2007 … The massiveness of the objects is produced principally by light, usually falling from the side and emphasizing their natural volume. A single light source is used, adjusted to the composition in such a way that the sharpness does not decrease with depth. Soft light predominates, bringing out sharp contours and pure masses of objects, without strong shadows and contrasts. The combinations of objects are (only apparently) simple, brought together in the artist’s subjective visual idea of the represented. However, as a rule, the positions are slightly shifted, deviated, slanted, or tilted, until they seem unusual, sometimes even defying gravity. This is where Gaberščik’s stilllifes come close to the realm of the surreal. In the compositions, the objects eschew ordinary, expected, or probable positions, producing images of an absorbed, mysterious atmosphere, where time has stopped, where memories are frozen, the objects stock still, and perception is transferred to the field of surrealist intirnism. Light is carefully controlled, admitted in such amounts that the objects do not have reflections, only gradual tonal transitions. This makes them appear elevated, full of a genuine natural power, belonging to a world of forms in which the photographer establishes and records a refined order. Such a controllable order is where Boris Gaberščik is most at home, working out his own system of portraits of objects drawn into a special psychological state of objecthood. This can be traced in over two hundred photographic still lifes, all evidencing his minimalism in the choice of motif and his perfectionism in relation to the medium of photography.

For Gaberščik, the only way to fathom the mysteries of photography is by personal experience gained in the process of work. That is why for him creating is a drawn-out process of preparing, choosing, composing, arranging, and uniting different objects. Many photographs bear deliberately indicative titles, emphasizing a crucial aspect of the motif, or the idea, or the structure of the composition. Thus, e.g., in the Orientation of the Tulip, 1987, a precarious balance is maintained between the slanting base and the flower in a vase which strives toward uprightness with some kind of inner strength. Some works give emphasis to the dynamic interplay of the objects’ positions, tilted angles, departures from real (expected) states of gravity: Arrangement for Irwin Penn, 1992, consists of a mass of elements that appear to have loosened up; Table with Toys, 2005, has a tall and narrow supporting structure on which cups seemingly hover in the air; and Magnolia, 2005, slightly (and only apparently) slides down an inclined surface. In some photographs, cubic and spherical elements are brought together, assembled and constructed in architectural ways: Cathedral, 2005, has strong plastic emphases and gives a sense of gravity shift produced by the contrasting of light and dark; in Temple, 2005, the illusory image overrides the realistic possibilities of such a construction; and Torso, 2006, reflects the silhouette of . a body inside a construction of massive elements. Also the more engaged photographs indicate fragility and transience, e.g., the State, 1994 and 1999, an unstable structure that could topple at any moment, or the Factory, 2002, an architectural composition of cubic elements, markedly narrative and reminiscent of the past. A great number of photographs, however, are Untitled; the photographer chose not to direct viewers with a title, allowing instead everyone to create their own story based on their personal experience. And Gaberščik’s photographs contain many stories, with the objects concealing the narratives of their use and “lived” functions in a certain time and place. The objects are brought to life with a certain kind of inner light, an inherent natural force that gives them meaning and another, profound, almost metaphysical character. This is observable in Grand Hotel, 1987, Left Flowers, 1987, Pencil for E. A. Poe, 1987, Wassermusik, 1995, Divided View, 1998, Nostalgic Look, 1997, Crushed Snail, 1997, Three Stars, 1995, Contemplation of Form, 2006, Knife on the Water, 2005, and Relic, 2006, among others.

Working in his studio, the photographer creates his characteristically ordered world of objects and presents it sharply and precisely, with all the necessary contrasts. Compared to such studio works, his photographs taken outdoors, in natural light, are far less sharp. Such are his photographs in the series entitled Atlantis, Arcadia, and Europe, 2005-2007. The titles themselves indicate associations with mythological (mystical) landscapes originating in the artist’s imagination and the real, tangible, definable Europe, in which he lives and works. The exterior world is enveloped in a hazy, mysterious atmosphere; real images push through and retreat, unfocused and blurry, into the realm of the fantastic, onto the road (which also stands out as a motif) of fairy tale play. The photographer says: “I’m through with dreaming of landscapes, the light keeps taking them away from me. It distorts them to a point beyond recognizability; noontime, like a youth full of himself and his budding power, heedlessly tears up surfaces, burns through patches of light, deepens the shadows to diabolic blackness, blends the horizon with the foreground, distances and fuses things, flattens and curves them, erases individual details, deceives and lies until the eyes are in pain. Instinctively I retreat out of focus, easing the speed, the harshness, and the irresponsibility, and look for more tolerable forms.” [3]

Nature is full of contrasts, which are much stronger outdoors than in the closed studio interior. When an image is transferred to a photograph, the contrasts, more difficult to control outdoors, diminish. But in his studio, Boris Gaberščik is the master of the fate of objects and their compositions, and of his photographic perception, totally sharp and with elaborate light and dark effects. The stilllifes are additionally irradiated by an inner light, as we can see in the photograph Grandfather’s Shirt, 2005, where the presence of the person can be felt in the folds and contrast creases of the fabric. The shirt has become a metaphor for the man, a psychological portrait of its wearer, more real than the man himself, motionless and alive at the same time.

Boris Gaberščik has been in the recent years combining photographs into diptychs and triptychs. He calls the series of such photographic works Dvojina (Dual), 2010, Trojina (Trinity), 2010, and Igra (Play), 2010. By such compositional procedure the photographer creates works of art as some kinds of finds, torn from the material world, from the world which surrounds him, and which for him signifies the strongest intuitive, symbolic, sensual and rational link with the past and the present. These photographic works are gradated or multiplied images of memory and representations with which the photographer explains both his fine art poetics and his innermost intimate world, in which he feels he is personally recognisable and creative. Gaberščik is exceptionally systematic photographer, his opus is extensive, balanced and faithfully follows the essential idea he has developed in numerous photographic images, namely that he studies, discovers and places images somewhere between the world of imagination and the world of reality, somewhere between the man as a subject with defined perception and the world of certain objectivity that surrounds him. It is this objectivity, with which Gaberščik photographs, that animates in an intensely felt way the man’s field of representation. The objectivity so characteristic for the photographer is a print, a trace of an object, an event which the photographer has torn from the particular flow of life, spellbound it into a graduated image. The photographed objectivity and its slightly different repetitions or combinations, as presented by these diptychs and triptychs, even approaches some »circular time of the magic of images«, in which – through photographic experiencing of the past time – the modern or present time of life, existence in general, is preserved or encouraged. The photographer explains and appropriates in his unique way the world with the images of objectivity, the depicted objectivity thus becomes a memory, symbolization of perception, in which the creator feels strong, as he ever anew encodes (embraces) the selected reality as certain concepts of the world. Both reality and imagination, which together form the freedom of a creative game filled with poetics characteristic for the author and with great creative force, balance and animate the world of images into which or through which moves the photographer.

It is this ability to bring the object world alive by capturing the minutest light, tonal, and expressive contacts between the material model (the subject) and the final image (the photograph) that makes Boris Gaberščik[4]so unique among Slovenian photographers. He is an artist who treats photography as a medium deserving a clear, systematic approach, with a great sense of responsibility toward its historical development, giving us food for thought and pleasure in observation.

Sarival Sosič, PhD

[1] Boris Gaberščik: Šahovska poteza za M. D. [A chess move for M. D.] Ars vivendi, St. 25, 1995, pp 95-96

[2] Sašo Scrott: Boris Gaberščik. Fotografija ni le “sklocanje”. Intervju. [Photography is more than just snapping away. Interview]. Slovenksa panorama, št. 6,2001, p.14

[3] Boris Gaberščik: Introduction. Boris Gaberščik. Ljubljana: Galerija Fotografija, 2005, leaflet [4] In his long career Boris Gaberščik has photographed a great number of works by Slovenian painters and sculptors. These photographs have appeared in monographs, exhibition catalogues, and other art publications.

1

of

5